A better way to culture microbes

Prof. Eran Elinav studies the interactions between gut microbes and the immune system, and how alterations in the microbiome can lead to susceptibility to common diseases and disorders, including inflammatory bowel disease, diabetes, obesity, cancer, and others. He is co-leading a personalized nutrition program based on clinical and gut microbiota responses to different foods. It is a challenge to explain the effects of particular commensal microbes on human health at a molecular level.

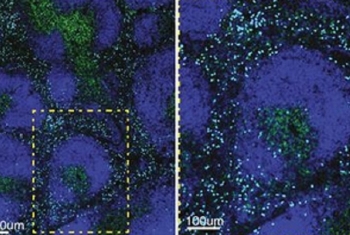

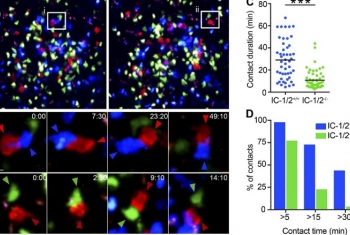

Prof. Elinav and his team has developed a miniaturized and multiplexed bioreactor system, that enables them to achieve high throughput calibration and to culture two hard-to-grow commensal strains at once, using the system’s 24 independent chambers of small-volume bacterial growth, with complete control of gas, temperature, pH, and other growth conditions. This system is revolutionary in allowing Prof. Elinav to gain a competitive edge in comprehensively studying discrete commensal microbes at a mechanistic resolution never before achieved.